A guided tour leads online readers through nine key areas of the collection, showcased by four examples each. Texts by members of our scientific team plot a brief timeline of the history of photography that takes account of a vast array of aspects relating to technology, media policy, aesthetics, style, and social history.

The 19th of August 1839, the day the daguerreotype was officially presented in Paris, is seen as the birth date of photography. In the following two decades the daguerreotype should prevail over other processes. An exposure of several minutes and a complex processing technique resulted in a unique, positive but inverted image in blackened silver. Its delicate quality appears best on close inspection under the right viewing angle. Due to its incredibly fine sharpness and unrivalled true-to-life level of detail the daguerreotype gained great success.

When the bourgeoisie began to have their portraits photographed instead of painted, it became the first commercially used photographic process. Standardised image formats were soon established, ranging from a whole plate (16.2 x 21.6 cm) to the 1/16 plate (4.1 x 3.4 cm). The specular reflective daguerreotypes on silver-coated copper plates were always framed under glass. Smaller formats were often mounted in leather cases with velvet lining. Cheaper processes as the ferrotype and the ambrotype replaced the daguerreotype in the second half of the century. OstLicht Collection houses c. 400 daguerreotypes, predominantly from French or American origins, including rare examples of early city views, clinical documentation as well as numerous stereo plates.

|

||

|

The family portrait in »full plate« format is not only framed in a magnificent stucco frame, also the photograph is of an outstanding quality. The composition is rich in contrast and clear-cut. The absolute neutrality of the image space is striking and it gives the daguerreotype a modern touch. There are no props, curtains, studio furniture or painted studio backdrops.

Four members of a family, most probably a mother with her three daughters are staged as a compact group. The similar dress style of the four women enhances an impression of uniformity and unity. As all portrayed wear black dresses, it is likely that it was a portrait taken in mourning. Perhaps the husband or father of the family recently died and the women wanted to have their portrait taken after the funeral. In the mid-19th century group portraits of families in mourning, which also included the dead relative, were quite common. Frequently mothers sit with their deceased babies to have their last picture taken in togetherness or they ordered post-mortem pictures, where the corpses of the beloved appear carefully decorated.

The elaborate stucco frame stands in contrast to the modern composition of this image. These frames were popular at the time and well known through painted portraits. Especially full plate daguerreotypes were framed and hung on the wall, whereas quarter and sixth plates would usually be kept in small collapsible cases.

Anna Zimm, © OstLicht

|

||

|

|

||

|

Most daguerreotypists earned their living with portraits. Studies assume that such assignments made up 90% of their total output. Portraits of children were especially challenging for daguerreotypists, as it was difficult to keep the curious and lively little fellows still for the necessary time of exposure. Notwithstanding, many portraits of children were made, and surprisingly often they are depicted as tiny personalities in single sittings.

The image above is a particularly sensitive and artistically fine executed children’s portrait. Shot on a sixteenth plate, therefore not much bigger than 2.5 cm in the width, it depicts a girl of about two years, wearing a dotted off-the-shoulders dress. The skilled lighting placed on the girl’s face and shoulders, as well as an unusual close up angle makes this portrait almost seem Pictorialist. A subtle colouration of cheeks and shoulders enhances this effect.

As the names of the photographers are engraved on the metal mount, the authorship of this image is clear – which otherwise is rarely the case in daguerreotypes. Together, James Earl McClees (1821–1887) and Washington Lafayette Germon (1822–1877) ran a successful portrait studio at Chestnut Street in Philadelphia between 1847 and 1855. McClees had begun to take daguerreotypes as early as 1844, though he always remained interested in new photographic processes as well as in the art of painting. After a fire in 1855, he opened a new and bigger studio in Philadelphia where he worked with a staff of 14 employees.

Anna Zimm, © OstLicht |

||

|

||

|

The stereoscope was invented in the context of research on the binocular depth perception. Charles Wheatstone introduced it in 1838 to demonstrate how the brain fuses the two slightly differing eye-views to one three-dimensional impression. Six months later, Louis Daguerre presented photography in Paris. Soon, the two novelties conjoined: since 1850 stereo cameras with two lenses were used in Paris and London, and stereo daguerreotypes were slid into the new lenticular stereo viewers presenting a magnified image with astonishing 3D effects.

After being apprenticed to renowned photographer Antoine Claudet, who had learned the craft directly from Daguerre and succeeded in London since 1841, Thomas Richard Williams became one of the most estimated photo artists of his time. He covered the first World Exposition at Crystal Palace, from where the boom of stereo photography started in 1851, in stereo daguerreotypes. His »The Launching of the Marlborough«, exposed from a moving boat in 1855, was highly praised as instantaneous stereo photography, managing to »freeze« the sea waves.

In this example Williams also shows motion, albeit by entirely different means. He positioned a stuffed cockatoo on a chair’s arm-rest, as if the bird is about to fly off, a chain with a valuable Chinese ivory ball in one of his claws. The dramatic arrangement has to be seen within the iconographic tradition of baroque still-life paintings, where various things, often combined with animals, are meant to address a maximum of the senses, reminding the beholder that all mundane will perish (vanity). Williams recognised the symbolic and aesthetic potential the genre could enfold in photography, by way this new media could be seen as oscillating between movement/life and standstill/death.

Both window and mirror metaphors, also previously discussed within historic art discourse, offer themselves for any contemplation on photography. Referring to them, Williams put a putative mirror in the foreground of his setting, partly covered by a lace shawl. Only when observed by the stereoscopic device, it clearly emerges that this is just an empty frame. Apart from his creativity in manifold visual references, Williams was also a skilful stereoscopic operator and image designer. That way he avoided overlapping, shadowing and blurring the outlines of the depicted objects for not detracting from a convincing 3D-effect. The definition and resolution of his daguerreotype are so fine that seven layers in the remarkable Chinese ball can be discerned. Marie Röbl, © OstLicht |

||

|

||

|

The Daguerreotype process was invented during the heyday of the industrial revolution, a period full of social and economic changes. Photographers captured the expansion of cities, the new iron constructs designed by engineers, the buildings of the world and industrial exhibitions and the newly built houses and shops on silver plates. Today, Daguerreotype outdoor location shots are rare pieces on the art market. If the quality is good, they sell for incredible amounts of money. Often, the photographer and the depicted location are unknown. As cities have changed a lot since then, it usually takes instigative skills to find out where an image was made. In the present case it is simpler. The stereo daguerreotype shows the main entrance of the Palais de L’Industrie in Paris. The palace was an exhibition hall, built for the World Exposition in 1855. Architect Jean-Marie Victor Viel, in cooperation with the engineers Alexis Barrault and Georges Bridel, designed the gigantic building between the Seine and the Champs Elysées. The image shows the monumental gateway at the centre of the 260-meter long main façade of the building, decorated by sculptures by Élias Robert and Georges Diebolt. In 1897, the Palais de L’Industrie was torn down to make way for the Grand Palais of the Exposition Universelle of 1900. The stereo daguerreotype by Disdéri is hence an important architectonic historical document.

Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri studied painting, which in those days was quite a common educational path for photographers, and then worked as an actor in a theatre troupe. In 1847 he opened his first own photo studio in Brest. In 1855, he received the commission to photograph all exhibited objects on display at the World Exposition in the Palais de L’Industrie. He took numerous stereo daguerreotypes from the exhibition halls inside and outdoor. Unfortunately, this success was short-lived. In 1856 he already had to declare bankruptcy and sell his studio. A few years later, he gained fame once more when his Carte-de-Visite process, patented in 1854, started to take off. In spite of his various talents and successes, Disdéri died blind, deaf and poor in Paris. Anna Zimm, © OstLicht |

When Frenchman Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and Briton William Henry Fox Talbot competed for the invention of photography in the 1830s, the negative as an intermediate step en route to the image seemed to be a disadvantage at first. Nevertheless, in the long run Talbot’s positive-negative process, named Calotype, proved itself more successful. It enabled a multiple reproduction of the image, and hence the expansive influence of photographic imagery on visual culture.

The earliest negatives were from paper, made light sensitive by silver salts and frequently waxed to gain more transparency. After exposure and fixation the negative was brought into direct contact with a sheet of »salted paper« to bear the positive. Other than the later materials for photographic prints, which were coated with light sensitive substances, the salted paper is mat and leaves the paper’s fibres visible in the image. The contact printing process took place in sun light and was finished with a fixation that could also manipulate the tonality of the image. As enlargements were not yet possible the print format had the same size as the negative, and the cameras in use were accordingly huge.

|

||

|

Since March 1858, the department documented the demolition of the baroque fortifications in Vienna. The broad wall with eight gates and ten bastions was a popular promenade for the Viennese during the 19th century. After the demolition the famous Ringstraßen architecture was constructed in the wall’s former place (and partly from its bricks). On the spot captured here Franz Josefs Kai was later built. The street in the foreground takes course from the Rotenturm Gate to the right, to Ferdinand Bridge. Gonzaga Bastion and the Elendsbastion run inwards the picture space. On the horizon the church Maria am Gestade can be discovered, to the right a row of newly built houses at today’s Schottenring. The wide panoramic view was possible due to a high vantage point from a tower of the nearby casern. The image illustrates Auer’s ambition of a photographic appropriation of the world, as he enunciated it in his writings.

A police officer is standing on the outermost part of the wall, before him is a builder working. Since the demolition is about to start, a barrier is erected here, documented in other images taken later. The incisive long structure next to the wall, with its side facade brightened by sunlight, was called the »Müllersche Gebäude« (demolished in 1889). It was home to the art cabinet of count Deym with replicas of sculptures from antiquity, real size wax figures, as well as music machines. The exuberant display of the pieces was very popular and the replicas were available for sale. This institution fulfilled an ideal that was similar to Auer’s vision for the k.k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei as a media enterprise: The combination of entertainment, education and advertising. In terms of media history this kind of cabinets and their artefacts soon became obsolete, whereas the climax of the photographic era was about to come.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

Lit.: Monika Faber, Maren Gröning, Stadtpanoramen. Fotografien der k.k. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei 1850–1860, Vienna 2005, p. 81.

|

||

|

|

||

|

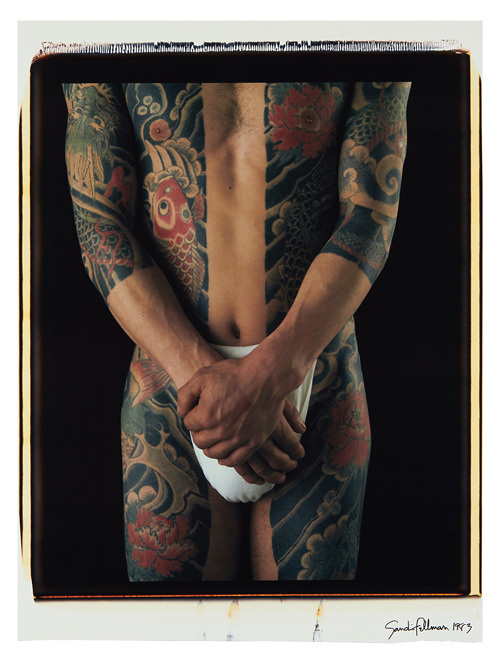

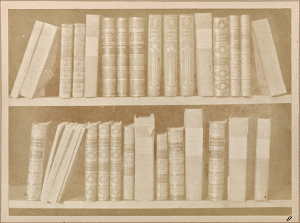

The image shows two narrow shelves filled with books and magazines on natural sciences and the humanities, such as The Philosophical Magazine, Botanische Schriften, Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians, Poetae Minores Graeci, and Lanzi’s Storia pittorica dell’Italia. The selection derived from William Henry Fox Talbot’s library, re-arranged in his garden. It is generally seen as an intellectual self-portrait of the private scholar. Prior to publishing his photographic inventions in 1839, Talbot was already a known author in the fields of mathematics, astronomy, linguistics, archaeology, botany, physics and chemistry.

Without doubt, Talbot’s most influential accomplishment was the invention of the positive-negative-process, patented in 1841 under the name of the Calotype. It was the technical precondition for the reproduction of photographic images. Being the first book ever illustrated with photographs, Talbot’s »The Pencil of Nature« was published in six instalments between 1844 and 1846. Every copy had salted paper prints glued onto its pages (more practical solutions for print reproduction were only developed in the second half of the century). His accompanying texts explicate the specific characteristics of the photogenic drawing and the wide spectrum of its possible applications.

»A Scene of a Library«, plate 8 of 24, can be compared to two groups of objects made from glass and porcelain on plate 3 and 4 – as well »additive« arrangements, that seem to be more in accordance to an archival order than to the aesthetics of the still-life. The potential to provide true-to-life records and comparative compilations of selected world fragments is crucial for the triumphant success of photography that follows. Talbot’s library scene may be seen as a predictive symbol for the influence photography would have on science and image culture, especially in its printed distribution. In the text accompanying the photograph Talbot underlines the capacity of photography to capture what is invisible to the eye, and he ends highlighting the probative force of printed matter.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

Lit.: Larry J. Schaaf, The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot, Princeton University Press 2000, p. 191; Hubertus von Amelunxen, Die aufgehobene Zeit. Die Erfindung der Photographie durch William Henry Fox Talbot, Berlin 1989, p. 31. |

||

|

||

|

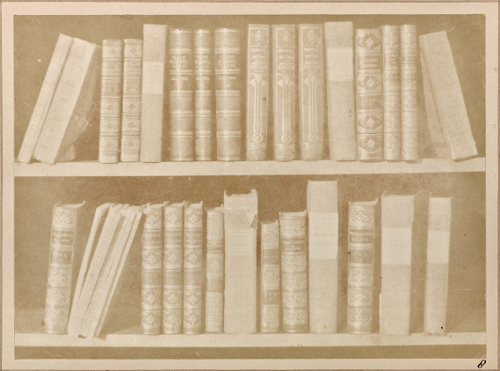

There is a close connection between the historical development of the museum as an institution and of photography as a medium of visual documentation: both serve the purpose of collecting, archiving and demonstrating, both create a new order for de-contextualised fragments of reality (removed from their real world and historical contexts). This connection can also be seen in the first Austrian publication illustrated with photographs, a catalogue of the armoury collection of the Habsburg arch duke Ferdinand von Tirol (1529–1595), written by Eduard von Sacken.

This collection of armour of significant monarchs and generals was established next to a library, a collection of paintings and a cabinet of curiosities (»Kunst- und Wunderkammer«) in the late 16th century at the Renaissance castle of Ambras in the Tyrol. The collection moved to Vienna in 1806 and is now located at the Kunsthistorische Museum, also including the half harness of the duke of Alba, crafted by Desiderius Helmschmied.

Andreas Groll was a pioneer of early photographic practice. Having started in 1852, he was one of the first professional photographers in Austria. He reached a high level of proficiency in many genres and techniques. His most renowned works are architectural shots taken in Austro-Hungary. This salted paper print shows extraordinary detail of reproduction, achieved through his experienced photographical technique as well as his skilled use of light and exact positioning of the object.

This also becomes evident by comparing Groll’s 150-year-old print with the present-day’s colourphotograph of the harness from the website of the Kunsthistorische Museum. The new photograph hardly shows the fine gravures on the chest plates of the armour, whereas in Groll’s already slightly faded print they are so highly visible, that the viewer can still make out a knight kneeling in front of a crucifix. The differences between the two photographs of the same object can also be read as an illustration of the change in standards and missions of museums and their visual mediums over the past 150 years.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Eduard von Sacken, Die vorzüglichsten Rüstungen und Waffen der k.k. Ambraser Sammlung in Originalphotographien, vol. 2, Vienna (Braumüller) 1862, table XXXI. |

||

|

||

|

This first static warfare in history became notorious for its bad logistics as well as catastrophic medical care for the troops, which was described in reports published in British newspapers. This is the context of Robert Fenton’s photographs from the first half of the year 1855, which visually rebut these allegations by showing palliating genre scenes and portraits (»picnic-war«). Besides that, his written records are evidence for the adverse circumstances war photographers of the Collodion era had to deal with.

James Robertson and Felice Beato finally documented the decisive phase of the war, the fall of Sevastopol. Robertson was a British engraver, who had been working for the Osman coin in Constantinople. In 1850 he also opened his photo studio there. He internationally published and exhibited his pictures of monuments in Greece, Egypt and Palestine, but his images of the Krim war remained his most prestigious work.

According to the annotation on its margin, this image shows a »bombproof magazine«. A labyrinthine system of trenches is cognoscible, marked by the specific basket cylinders used for the fortification of earthen walls, on the horizon an army tent. As it is a known fact that Robertson photographed the occupied Russian positions in Sevastopol, it can be assumed that these are the systems of trenches, batteries and dugouts that the Russian engineer officer and later general Eduard I. Totleben had commissioned for the fortification of Sevastopol. Bombproof durability was very important during this war, since a great deal of ordnance was applied, as bomb cannonry was used for the first time for defence against ships. Marie Röbl, © OstLicht |

Already in its early stages, photography was employed to document architectural and natural monuments in foreign countries, as its true representation of reality allowed sightseeing without travelling. Due to various (e.g. technical) reasons candid photographs of everyday life and of people from other cultures stayed rare, but staged studio scenes gave first impressions.

Technical innovations after 1850, as the collodion wet plate process or the use of albumen paper prints, considerably improved the image sharpness and made close observation of photographs even more appealing. The wet plate process did not make exposure operations easier for the travelling photographer, but it simplified the production of multiple prints at the copy workshops. A bustling market for depictions of landmarks and urban views (»vedute«) developed along the main stations of the Grand Tour, especially in Italy. With the beginnings of mass tourism photographs and photo albums became popular travel souvenirs. OstLicht Collection holds numerous travel albums, including more than 10.000 pictures, predominantly from Europe, Africa and Asia.

|

||

|

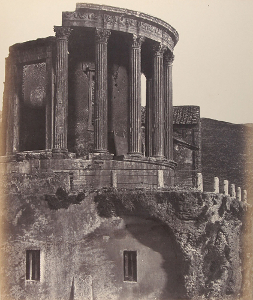

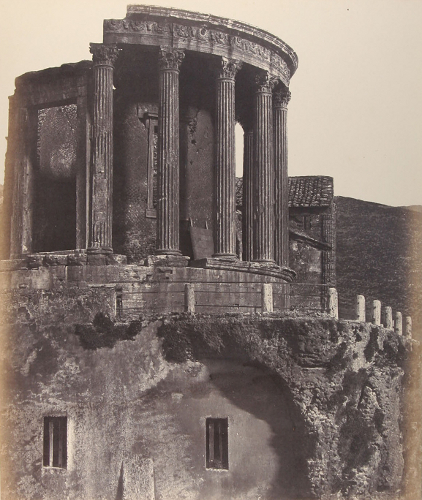

Before he relocated to Rome in 1840 and devoted himself to painting and art dealing, Scottish born Robert Macpherson worked as a trained surgeon. In 1851, he learned the new Wet Collodion process with glass negatives in the format 12x16 inch (c. 30x40 cm) and soon became greatly skilled. The educated, bourgeois tourists of Rome appreciated especially his »vedute« of sites from antiquity. The so called »Temple of Vesta« on the Acropolis in Tivoli is a Roman circular templewith Corinthian columns. Since the early 18th century, the antique edifice aroused great interest from classicist architects, who took it as a model for numerous structures and copied its details. Furthermore, it was an ideal motif for visual artists, especially from a greater distance, showing the round temple ruins in their spectacular environment with cascading gorges and waterfalls. Like his customers Macpherson was certainly aware of the prominent reception history of the temple, and he offered several views of it.

This image deviates strikingly from the well-known iconography of painted forerunners. Macpherson’s tight cropping of the architectural motif »objectifies« it. He reduces the dramatic, and the spatial effects of a subject matter that was just characterised by its picturesque topographical features – the round temple on the outmost cliff of a fissured, vast rocky ground. Macpherson’s concentration on the structure, positively cut out from its environment, is an eminently photographic image design of modernist appearance, seemingly anticipating later movements as the New Objectivity.

In comparison to the more conventional postcard motifs taken from a wider angle (and taking more sky and terrain into the image) in the following decades, this modernity also becomes evident. When in the 1860s it became more and more popular to sell Roman cityscapes Macpherson kept his exclusivity, limited his editions and refused to sell his images on the mass market. Today his delicate large format prints are still sought-after collectibles.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

|

||

|

|

||

|

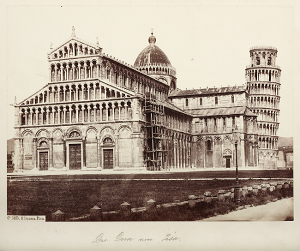

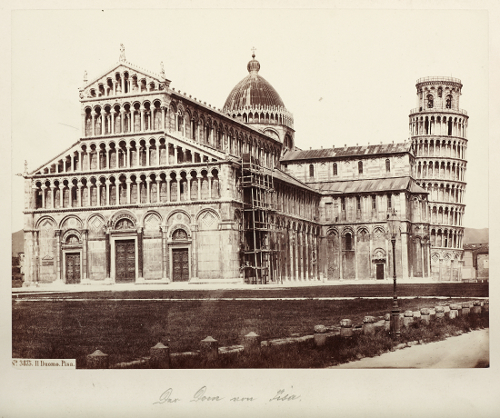

German-born photographer Georg Sommer moved to Italy in 1855. There he became one of the most renowned photographers of Italian landscapes, monuments and art. He sold photographic prints in all kinds of formats, including carte-de-visite and stereo-cards to tourists. Having started up in Rome, he moved to Naples in the late 1850s and opened a studio there, where he mostly worked on genre scenes. From 1880 on, he started to take open-air pictures on the streets. His photographs of the Pompeii excavation sites and of the Vesuvius eruption in 1872 are also well known.

This image at shows the dome of Pisa with its crooked tower, a classical tourist attraction, frequently photographed. The huge empty space around the dome allows manifold perspectives on the structures. Sommer’s composition distinguishes itself from many others by its combination of the two edifices into one compact shape emphasising the orthogonal lines. Strong contrasts accomplished by a dark violet toning accentuate the surface of the architecture.

The various inscriptions indicate Sommer’s professional distribution channels. First, a label on the glass negative, printed in white letters on black paper, which can be seen on the lower left of the positive shows that there was a commercial negative archive. An employee in the capital city with its large market managed this archive not only for tourists but also for the circles of international artists. Second, the stamp on the cardboard’s lower right mentions the branches of Sommer’s business in Naples (and also allows the dating of the print): The address mentioned is Monte di Dio 4, where he ran his studio between 1860 and 1886, and Megazzino S. Caterina, where he owned a storage space. Third, another stamp in the middle of the board refers to the German dealer J. Brecker, who distributed Sommer’s prints in Florence.

After all, the handwritten title in pencil lets us assume that a German-speaking customer once purchased the print. Especially the German Bourgeois favoured Italy as a relatively close and convenient travel destination. This journey promised the combination of education and recovery in the Southern climate, as well as personal self-development of the kind paradigmatically described by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Giorgio Sommer in Italien. Fotografien 1857–1888, ed. by Marina Miraglia, Pino Piantanida, Ulrich Pohlmann, Dietmar Siegert, cat. Munich 1992. Giorgio Sommer (1834–1914). Photographien aus Italien, cat. Neue Galerie der Stadt Linz 1985, p. 40 (ill.). |

||

|

||

|

In 1854, the USA enforced Japan to sign commercial treaties in a colonially offensive manner. After centuries of solitary insular politics, Japan opened itself to western progress in the wake of the following trades. After a change in power and the beginning of the Meiji Restoration from 1868, the development of Japan into an industrial nation went extremely fast. In contrast, the Japanese remained true to their cultural traditions. Photography was long seen as a sacrilege, it was feared for stealing people’s souls and western travellers were not allowed to take pictures.

Photography only started to establish itself around 1880, when its style was adapted to Japanese culture. Artificial settings in the studio, a range of selected genre scenes, portraits and canonical landscape views were the prevailed subjects. Their designs often followed the Japanese colour woodcut (Ukiyo-e). The delicate colourisation of the prints derived from Ukiyo-e. It became a significant attribute of Japanese photography spreading to Europe over the travelling albums of Western tourists. The albums made from lacquered wooden boards, hand-painted, and with mother of pearl inlays were also a popular souvenir from Japan.

OstLicht Collection holds a substantial number of albumen prints from the travel albums of tenor Anton Schittenhelm (1849–1923), who was a member of the ensemble at the Viennese opera house. This photograph shows two Japanese women staging a welcome scene at a photo studio. It stands out for the exquisite colour range in the painted kimonos. Typical for the polite greeting ceremony on visits are the deep bow with hands on top of another, the preparations for tea brewing, and the present for the host (lying in the foreground). Apart from that, there are selected fragments of Japanese ambiance like tatami mats, an ikebana flower arrangement, and a painted folding-screen (byobu).

The print stems from a series that Schittenhelm very probably bought in Yokohama, where most of the western tourists arrived and departed and where many studios were established. Besides the motif at hand, the series includes scenes with geishas playing instruments and drinking tea. The quality of the painting and the set decoration remind of Kimbei Kusakabe (1841–1934) – thus this work may be attributed to one of his students. Marie Röbl, © OstLicht |

||

|

||

|

Before 1900, Australian aborigines were rarely photographed outdoors. Instead, they were often depicted anonymously in photo studios, in front of backdrops with painted »wilderness« and with traditional clothing and attributes. Between 1870 and 1890, stereotypes – such as warrior, young girl or mother with child – were produced in their thousands for the commercial market. The contemporary European public regarded the allegedly anthropological photographs as realistic depictions of people and scenes from their everyday life.

In contrast, this outdoor shot portrays a named inhabitant of the Lake Tyers area in front of a windbreak built of branches and shrubs. William Bull was the father of Hector Bull from the same region painted by Percy Leason in 1934. The depiction is closer to reality than the above-mentioned studio photos. The man is wearing trousers, shirt and waistcoat, which was often the case as soon as indigenious people came under the influence of European missionaries. However, the photographer was not able to escape the convention of depicting him with traditional Aborigines hunting equipment (boomerang and spear), even though William had most probably already given up his nomadic life to earn his money as a labourer.

Whites appropriated Gippsland on the south coast very early. The massive colonisation of Australia reduced the Aboriginal population from an estimated 750,000 at the time of first contact with Europeans in 1788 to 67,000 in 1901. Imported diseases, land theft, and belligerent acts caused this systematic decimation. A large majority of those who were driven from their land were re-settled in reserves and mission stations. Many lived in the periphery of the rapidly growing cities and earned a poor living with jobs in agriculture as shepherds or sheep shearers, and as servants (roles, in which they were rarely photographed).

Nicholas John Caire worked as a barber in South Australia since 1858 and became a professional photographer in 1867. He moved to Victoria in 1870 where he worked as a photographer and barber in the gold mining settlement of Talbot. The following year he was able to open a studio in Bendigo, a larger town where he sold his carte-de-visit portraits and landscape pictures. His main interest was art and this led him to paint as well. He is regarded as one of the precursors of the Pictorialist movement, in that he enhanced formal group portraits by genre scenes or landscapes by picturesque effects or anecdotic byplays. This corresponded to a growing demand of images to support the process of building an Australian national identity.

Ulla Fischer-Westhauser, © OstLicht

|

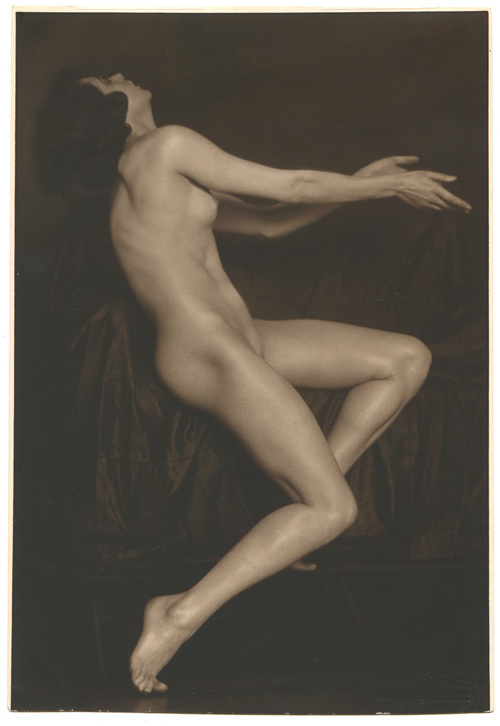

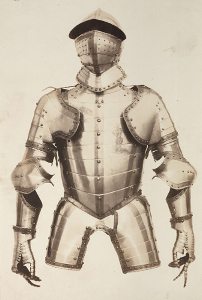

Photographs of the nude body were not socially acceptable until the end of the 19th century. Prior to this they were rarely published, though frequently produced and distributed. In looking at examples of this genre, specific features and discourses of the photographic medium become strikingly evident. The inherent referentiality of the photographic image, its specific connection to the depicted subjects and scenarios, affects its reception. Hence, pornographic effects may come into play, when secret or tabooed subjects are represented.

Considered within the wide spectrum between commerce and art, nude photography shows distinctive variations, ranging from the mere auxiliary function of photographs for academic painters to an essential issue of fine art photography. Here, emphasis is put on aestheticformal qualities, e.g. in the representation of materiality (skin, fabric) and in the modelling of physicality by subtle contrasts of light and shadow. Furthermore, crucial dispositifs of society, such as gender roles and »disciplinary« effects on the body manifest themselves within this genre – the status of the photographic image is fundamentally at stake, as a document, and also as an instrument of social constructs and power.

|

||

|

Anton Josef Trčka was born the son of Czech immigrants in Vienna. He started his artistic education in 1911 in Karl Novák’s photography class at the Grafische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt. Apart from his efforts as a photographer he was also a gifted poet, painter, sculptor and artisan. From an economic perspective his career was not very successful, and his later reception was hindered when a bomb strike hit his studio in 1944, destroying almost his entire oeuvre. Today his works are academically renowned and do well on the art market.

The question if photography is a commercial craft or a genre of the artistic canon was heavily discussed in the years after the turn of the century. The Jugendstil movement found a way of combining the so-called professional photography and the amateur or art photography. Trčka’s most important role models were Schiele and Klimt, his highly artistic ideals show in his artificial image staging, as well as in the references to pre-Raphaelite and symbolist art.

Trčka had been working at the studio of photographer Hella Katz, situated on the Viennese Stubenring since 1925, where he founded the »Ringwerkstätten für Kunsthandwerk und Lichtbildkunst« in 1926. The workshop closed in 1934. Besides working on nudes and dance studies, he portrayed his poet and musician friends from the anthroposophist society, for whom he also organised recitals, lectures and eurythmic dance events.

The nude in this image shows his artistic position quite clearly. The influence of Jugendstil manifests itself in the formalised figure, through a closed swinging outline, sheets are draped around the stretched out figure, the fabric on the back rest of the piece of furniture was designed by Trčka himself. A potted plant is carefully placed in the picture. The image is accentuated by several graphic elements added on the negative. They show as white lines in the print, most clearly visible close to the head of the woman, but also next to her elbow on the left side of the image, as well as on the flowerpot.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

Lit.: Monika Faber, Anton Josef Trčka 1893–1940, ed. by Rupertinum, Museum for contemporary and modern art, Salzburg/Vienna 1999, p. 105.

|

||

|

|

||

|

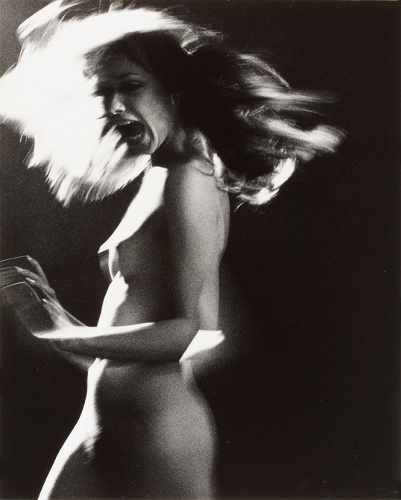

Trude Fleischmann represents a generation of rising female photographers who opened modern, urban portrait studios in the 1920s, after having received their education during the First World War. Thus, they conquered a masculine domain that offered economic success within a creative business. Since female students were allowed to attend the photo courses at the »Grafische Lehr- und Versuchsanstalt«, significantly many women from liberal Jewish bourgeoisie pursued this profession in Vienna. After two decades of successful work, many of these studios were closed with the Anschluss, and many of their Jewish owners - mostly fromassimilated,long-established families were deported by the Nazis or had to take refuge. Under the Viennese Jewish photographers, Trude Fleischmann was one of the few that were able to emigrate and continue their carrier (hence, all her negatives were lost). OstLicht Collection houses more than 240 vintage prints from her time before 1938.

After a 6-year-long professional education Fleischmann opened her studio in 1920, where she became a popular society photographer. Apart from her sales to the customers she published in numerous magazines and contributed to exhibitions, and agencies distributed her pictures, too. As many performing artists were among her clients, the role portraits and dance studies suggested themselves for another focus of activity. To evaluate her nude photographs with the Munich dancer Claire Bauroff, one has to consider the contemporary heyday of modern dance in Vienna, the movements of »Lebensreform«, naturism and nudism, as well as a new concept of women’s role in society.

Model and photographer were both 30 years old when this cooperation took place, and both paradigmatically embodied the new woman. Bauroff was a modern »Ausdruckskünstlerin«, educated in rhythmic gymnastics, modern dance and performing arts. She emerged with her part in a play of Frank Wedekind and with a dance drama, that she wrote and choreographed herself. In Fleischmann’scomposition Bauroff’spose appears as the perfect balance between energetic tension and devoted dedication to the performed expression. No props, no anecdotic title, no irritant gaze invites the (male) observer to get hold over a desired (female) object. The position of the figure within the picture format follows exact diagonal and orthogonal lines, thus emphasising a stability that is readable as autonomy. This effect may be one reason why these nude photographs caused a scandal.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

Lit.: Frauke Kreutler, Berlin Scandal. Trude Fleischmann Sets the Stage for Dancer Claire Bauroff, in: Kreutler, Holzer (ed.), T. F. Der selbstbewusste Blick, cat. Vienna Museum 2011, p. 104–118. |

||

|

||

|

Sam Haskins was one of the pioneers of nude photography during the 1960s. He worked in Johannesburg, South Africa until 1968, when he moved to London. His work was seminal for graphic designers and photographers alike, for example Jeanloup Sieff or David Bailey, but also influential for developments in the cinematographic imagery. Haskins preferred to photograph girls that were not from a professional modelling background and would pose naturally and confidently, sometimes moving, in front of his camera. He frequently used blurriness and grainy coarseness as essential means of his image design.

Haskins’ interest to shape his photography’s reception by contextualisation, a performative element, is also characteristic for his work. He often showed his photographs accompanied by music in feature-length slide shows with up to 500 medium format images. His two most successful photo books, »Cowboy Kate« (1964) and »November Girl« (1966) include narrative spreads and montages of nudes and landscape photographs. In an up-to-date graphic design the story unfolds exclusively by the images, their combination and organisation.

This picture was taken in the period these books were published. Studio lights and blurring by movement are used to great effect. The photograph reminds one of certain images in »November Girl«, such as of the famous »black rain coat series«. In addition, the evocative, supposedly screaming expression of the girl is to be found there.

With images like these, the history of nude photography started a new chapter, aloof from formulaic pin-ups or classic studio shots. When gender roles slowly began to change, women were still the object of a covetous male gaze. Hence, women remained also a motif for photographic depictions of these power relations.Yet after all, an extended space to move seemed to have opened up, a new freedom reflecting a movement known as the sexual revolution.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

Lit.: Sam Haskins, November Girl, London 1966. |

||

|

||

|

Born in Minowa, Tokyo, Noboyoshi Araki today is one of the most widely known photographers from Japan. He studied photography and film at Chiba University. Later on, he worked as a photographer for advertising agency Dentsu, the biggest of its kind in Japan. While working there he already followed his own photographic passions in private. He took images of his hometown and its inhabitants, as well as of his female colleagues.

His body of work is immense. He is manically documenting his everyday experiences and organises the images in sequences, publishing them in a diversity of ways, in books or as »Arakinema« (a movie compiled of single images), in public space, at noodle restaurants or in galleries or museums. His photographs are shot in the documentary-biographic Japanese style of the »I novel«. This genre uses realistic representations of events in the life of the author as the basis for a fictional story line, also paradigmatically reflecting social conditions. Araki describes his use of the medium as »I photography«.

This is also the context from which his erotic photographs emerge. For Araki photography is inseparably connected to verbal and physical interaction with his model. The act of taking a photograph is an erotic experience for him –a way to relate to his model via his camera. The bound woman is a frequent subject. Kinbaku, a Japanese version of bondage, has its origins in the tradition of the martial art of Hojojutsu. During the 19th century, the bondage technique in an erotic context was spread via wood cut images of the Edo period.

This photograph was published in Araki’s book »Sentimental Voyage« as part of a sequence with landscape views, flower still-lifes, images of Tokyo, his apartment, and portraits of his deceased wife, mixed into a diary-like visual aggregate.

Michaela Seiser, © OstLicht Lit.: Nobuyoshi Araki, Sentimental Voyage, Prato 2000.

|

Since the beginning of the 20th century press professional photographers increasingly took over the role of the graphic illustrators, likewise bound by instructions from the magazines’ editors. Published by printed mass media, photographic images gained widespread effect and influence as never before. They shaped the perception and collective memory of events and public figures. On the other hand, the supposed objective truth of photography made it also a convenient propaganda tool for political interests, though.

In the interwar period, editorial photography had its first golden age. International picture agencies began dealing and distributing of daily press photographs (whereas the copyright of the image author was often ignored). New 35mm cameras and roll films with increased light sensitivity made it possible to shoot almost anywhere. Therefore, a new technology set the stage for photojournalists to create new picture designs and a new self-conception as image authors.

|

||

|

The original agency text from the Californian office of World Wide Photos on the reverse of the photo is as follows: »All the acrobatics known to aviation can be performed on this queer aeroplane just given its debut at Los Angeles, with the added advantage of the danger being absent. Equipped with standard controls, and powered by an electric motor, it loops, banks, turns at its safe altitude of a few feet, and is said to be invaluable in teaching student pilots the rudiments of flying«.

On 27th April in 1932, the picture was released in the left wing Vienna newspaper »Der Abend«, its editors changing the caption into: »In the flying school of Los Angeles, California, a major site for American aviation, new equipment has been introduced. It trains student pilots in the shortest possible time to get used to heavy draught and to overcome vertigo. – Such training to stay free of dizziness and vertigo would also be appropriate for Austrian bank directors«.

The final sentence was intended to underline the massive bank crisis that took place in the Austrian banking sector from 1930 on. It culminated in the collapse of the Creditanstalt. Between 1931 and 1933, the state and the National Bank had to provide over one billion schillings to support the Vienna banks. The resulting economic crisis made 1932 the blackest year of the first republic. Writer and journalist Carl Colbert (1855–1929) founded »Der Abend« during the First World War as a Marxist, socio-critical daily newspaper, an early tabloid press with focus on local politics. In every copy the paper included a pictorial page. Its images, accompanied by short, often polemic captions, had no relationship to each other and were independent of the articles in the rest of the paper.

The image authors of editorial photography, in this case very probably an American press photographer, stay mostly uncredited, as they have passed their copyrights to the agencies. Wide World Photos is the photo agency of Associated Press (AP). The print shows the editor’smarkings in the margins to define the required cropping. In addition, retouching can be clearly seen, undertaken to increase the image contrast since the print quality of the newspaper was limited. The photograph demonstrates these historical contexts of use and adaption. It stems from the archive of the important Austrian paper »Arbeiter-Zeitung« (since 1970 released under the name »AZ«, shut down in 1991), obviously having over-taken older holdings.

Ulla Fischer-Westhauser / Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

|

||

|

|

||

|

The photographer took this image from scaffolding installed on a building in Vienna, at Schlachthausgasse 2, on the corner of Ludwig-Kösslerplatz. Other photographers were in place on both sides of the bridge. The photojournalist Fritz Zvacek (visible left from the image centre) even stood on top of a mechanic ladder to take pictures of the potentially spectacular event.

The Kaiser Josefs Bridge had been built for the world expo held in Vienna in 1873 and was renamed Schlachthausbrücke in 1919. It was the first connection between the third district and the Prater. This bridge with an effective span of 60 metres and a roadway width of almost 10 metres was not adequate anymore during the time of the first republic, when sports activities and the opening of the stadium in the Prater increased traffic considerably. The previously realized Rotundenbrücke was the model for the plans for the new Schlachthausbrücke. The design and implementation of the iron construction was executed by the Wiener Brücken- und Eisenkonstruktions AG in cooperation with the company Ing. Mayreder, Kraus & Co, responsible for the architectonic design of the bridge. With an effective span of 55 metres and a roadway width of 12 metres the new bridge offered enough space for two tram tracks and two car lanes. It was opened for traffic in 1937 and cost 2,4 million schillings to build. It was destroyed in 1945 during the Second World War.

Almost hidden in the forest on the opposite riverbank the settlement Wasserwiese is detectable. The buildings on the right side belong to the depot of the Vienna State Opera, which until the end of the monarchy had been used as the k.k. Court Fourage Depot (horse food depot).

The position of the cars shows that at the time Vienna was still driving on the left side of the road, as was customary during the times of the monarchy. In the first republic this caused a lot of confusion, as in some of the federal states left and right side traffic was allowed, signposted in several languages. The general decree for the use of the right side of the road was decided in parliament in 1929, but was not implemented everywhere right away. Especially Vienna refused the new rule for a long time, referring to the immense cost and complication of adapting the infrastructure of the trams to the new side of the road. Only in 1938, after the Anschluss, the right hand side traffic was finally implemented.

Ulla Fischer-Westhauser, © OstLicht

|

||

|

||

|

The press photographer’s job profile and concept culminate in the task of war photography, as the profession’s demands and myths become notably obvious. As the »invisible observer« the photographer dives into the course of events. He registers them, supposedly neutrally, with an almost internalised apparatus. The photo-hunter reveals his virtuosity in reacting all but automatically, at the decisive moment. In creating seemingly authentic pictures, the paradigm of the documentary admittedly requires high efforts from the image author as well as from the editor, e.g. by using effective blurring or framing. The creation of a war photograph stands in the service of a dramaturgy that has also be able to communicate chronological, causal, or other contexts that are related to a captured moment.

Originally trained as a hairdresser, followed by a stint at a photographiclaboratory, Walter Henisch began working as a freelance photographer in Vienna in 1932. After engagements for the »Hitlerjugend« he became a war photographer for the German Wehrmacht. He covered important war zones in Poland, France, Russia, and at the Balkan Peninsula. Besides his official commissions he also took pictures of the occupied areas’ population, as well as landscapes and cities. After the war, while he continued to photograph professionally until the 1970s, he created elaborate albums from his war pictures he mainly showed privately, accompanied by telling his war experiences. Encompassing of more than thousand prints, these albums from his war years are now held by OstLicht Collection.

The photographer’s son, author Peter Henisch, worked his father’s past into a novel, including a quote from Walter reporting the genesis of the picture at hand: »To cross a railroad embankment that the Russians were shooting at in waist level (…), was nothing but Russian roulette. First, the group lies under cover, that is one image. Another image: The strained tension visible in the faces. They jump up and head off – soldiers that run, some duck – some collapse – some scream (…). A series of 20 to 30 images. Exposed by me. My capacity of estimating light and movement conditions has already turned to instinct. In the next shelter, I will develop these images«.

Shortly after the beginning of the attack on the Soviet Union, the Wehrmacht started the offensive towards Smolensk, where the Red Army had built new lines of defence. In the process, big parts of the Red Army were enclosed. Even though the advance on Moscow, which was planned to be a »Blitzkrieg«, was delayed, this battle of encirclement and annihilation was a success for the Wehrmacht and caused terrible loss at the Russian side. Overall, 760,000 Red Army soldiers died during the two month-long operation at Smolensk in 1941.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht

Lit.: Peter Henisch, Die kleine Figur meines Vaters, Vienna 1975, p. 95 (quote); Christian Stadelmann / Regina Wonisch (ed.), Brutale Neugier. Walter Henisch, Kriegsfotograf und Bildreporter, cat. Vienna Museum, 2003, p. 57, 36.

|

||

|

||

|

The Hahnenkamm races, nowadays the climax of the annual ski circuit in Austria, first took place in 1931. At that time, there was no course fixed and the locations switched a number of times within the Kitzbühel skiing area in the Tyrolian Alps. It was not until the 1950s that the now famous »Streif« and the »Ganslern« became established as a fixed part of the Hahnenkamm race. In 1937 the race was held for the first time at the »Streif«, considered to be one of the most challenging downhill slopes in the world. Later, sections known as »Startschuss«, »Mausefalle«, »Steilhang Einfahrt«, »Alte Schneise« and »Hausberg« were added.

This reportage photograph shows the changes in equipment and conditions over the sixty years since the beginning of the race. As the racers participated in preparing the slope, warming up was unnecessary. Getting to the top of the slope was accomplished by walking, clothing was anything but aerodynamic, and helmets were also still unknown. In 1948, Hellmut Lantschner from the Tyrol won the downhill event and came third in the slalom. Officers of the British occupying forces also took part in the race, and members of the Dutch Ski Association were in with a chance too!

There was great international interest in the spectacle even in 1948. Reports in the newspapers and on the radio were released, and athletes gave live interviews. Press photographer Ernst Hausknost was not a specialised sports journalist. In the 1940s and 50s, he was a still photographer for Austrian film productions and the Salzburg Festival employed him after the Second World War. Apart from that, he ran a studio in Fuschl and, as a freelance photographer, contributed his stories to various Austrian and German newspapers and magazines. Between 1955 and 1960 he was the staff photographer for the Ronacher variety theatre and the Stadttheater in Baden. He also worked for the Reinhardt Seminar and the Löwingerbühne. From 1957 until an advanced age (1992) he was the employed photographer for the Josefstadt Theatre. He portrayed numerous Austrian artists and actors. OstLicht Collection holds 250 prints from his estate.

Ulla Fischer-Westhauser, © OstLicht

|

Since the 1920s, photojournalism had gained considerable influence in magazines, whereas the importance of unillustrated articles was on the decline. Until television took over as the main visual mass medium, photo reportage experienced a huge boom during the years after the Second World War. Not only the felicitous shot was in the limelight, but also the photo spread illustrating or telling a multifaceted story.

Most of the new photojournalists considered themselves as independent image authors. Their point of view and »Weltanschauung« is manifested in critical or provoking photo essays. Their images question myths, and their photo spreads tell stories full of humour, irony or melancholy. Pictorial reports on public figures and celebrities not only show a glamorous image, but also attempt to depict the individual person in their daily routines. Terms like »human interest« or »concerned photographer«, deriving from members of the legendary Magnum agency, describe this new attitude. The influential show »The family of man« also reflected the underlying hope to move society by the universal language of photography. More than 50,000 pictures at OstLicht Collection were originally produced for use in print media.

|

||

|

When Franz Lehar died in his villa in Bad Ischl on the 24th of October in 1948, his death mask was cast, following a traditional rite rooting far back into ancient times. Another comparatively young tradition was upheld by taking a post mortem photograph. Both traditions fulfil the wish to record the ephemeral to save its significant features from sinking into oblivion.

The production of a death mask was only available to a small group of people, whereas the spread of photography enabled wider circles of society to keep their dead’smementos. Certain photographers were specialised on producing the final image of people. Until the 1930s it was common to lay out the bodies of dead people in the family home. Pictures of relatives around the deathbed and photographs of affectionately adorned bodies of children or infants were kept in the family albums next to usual portraits. Only the advent of modern society declared death a taboo.

Franz Lehár was born in Kormon (Austria-Hungary, today Slovakia) and was a distinguished composer of operettas. His early success enabled him to devote his time exclusively to his compositions and to conducting. His fame surpassed that of Johann Strauß. The bed and even the small pillow on which the head of the composer was resting during his last days are on display at the Lehar Villa until today.

Erich Lessing was born in Vienna in 1923 and had to flee to Palestine in 1938, where he worked as photographer for the British army. After the war he returned to Vienna and became a press photographer for the Associated Press Agency, establishing himself as an internationally renowned photojournalist. In 1950 he was accepted as a member of the legendary Magnum photo agency, founded by Robert Capa, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and George Rodger among others. In 1956, he was the first foreign photographer in Budapest, documenting the Hungarian uprising.

The Viennese make-up artist Willi Kauer (1898–1976) was a renowned specialist for documentary masks for anatomy, forensic medicine, theatre and for the production of living- and death-masks. In 1948, he bought an old colour metal mask from Jakob Jelinek, which he identified as the death mask of Mozart that had been lost for 157 years (a find that remains highly disputed until today).

Ulla Fischer-Westhauser, © OstLicht Lit.: Alistair Crawford, Erich Lessing, Vom Festhalten der Zeit. Reportage-Fotografie 1948–1973, Vienna 2002, p. 55.

|

||

|

|

||

|

One of her first assignments for Magnum led Inge Morath to London, where she worked on a photo story for »Holiday Magazine«, portraying the inhabitants of Soho and Mayfair. The portrait of Eveleigh Nash with her chauffeur at the Buckingham Palace Mall is one of her most well-known images. It was published many times and different prints of the image are held by renowned collections.

The complex composition seems to have two perspectives with different vanishing points. The distinguished woman in her open limousine is connected to the background by parts of the coach that form a sort of framework for the minor characters in the image. The chauffeur and the two male pedestrians on the boulevard are the protagonists of this mise-en-scène. As framing is always a form of demarcation, it can be argued that the image structure of this photograph illustrates certain social contexts.

In the gaze of the portrayed – the chauffeur and Mrs. Nash are both looking into the camera – another ambivalent relationship is uncovered, the one between the portrayed person and the photographer, including the way the latter uses her apparatus. Insofar as we can detect the reactions of the portrayed staged within the pictorial space, Inge Morath as the photographer becomes perceptible in the image too.

Morath’s working method is visible in a somewhat distanced yet focused attention for her subject. This is a typical trait of her work, as she always tried to get to terms with the subject before committing to a photograph. She was never interested in speedy capture, or in spectacular and revelatory moments. Four metres of distance and a 50 mm lens were her preferred optical characteristics.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Kurt Kaindl (ed.), Inge Morath, Fotografien 1952–1992, Salzburg 1992, p. 12, 65; Olga Carlisle, Große Photographen unserer Zeit: Inge Morath, Luzern 1975, p. 24f (cover).

|

||

|

||

|

Franz Hubmann realised that reports on art are the most appealing when told from the perspective of a direct contact with the artist. Consequently, he went to Paris, in the middle of the 1950s still the undisputed centre of the art world, and portrayed more than twenty leading artists in their studios or homes, including Jean Tinguely, Hans Hartung, Hans Arp, Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Le Corbusier, Alberto Giacometti und Wassily Kandinsky.

It was essential but difficult to meet Pablo Picasso. Though Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, the legendary art dealer and intimate of Picasso for decades, assisted Hubmann with general research, he refused to arrange a visit in Cannes, where the famous Spaniard used to live in his »Villa La Californie« since 1955. Hence, Hubmann set off to the Côte d’Azur on his own and was lucky. Picasso willingly invited the Austrian photographer – who to his surprise found that Kahnweiler was also there!

This image also tells this context. It represents Picasso and Kahnweiler sitting in Thonet rocking chairs, engrossed in a conversation. Walls and tables show characteristic indicators for the famous artist’s work, the open garden door leaves in Mediterranean sun light, drawing the figures in stark contrasts, which for instance show Picasso’s eyes in significant sharpness. An empty chair in the foreground, cropped by the lower image frame, serves as an ambivalent element: it points to the interlocutors and can be read as an invitation to contribute - though also symbolizing distance as the backrest has the form of a fence.

Franz Hubmann started his education and second carrier as photojournalist in his thirties, after working in a factory and his call-up for the Second World War. Within a few years after the war he gained great success as a modern »life«-photographer and editor, and was called the »Austrian Cartier-Bresson«. He had essential influence on succeeding generations, also by his work for Austrian television. In 1970 he used his portraits of the French art scene for the TV feature »École de Paris«, for which the art historian and renowned curator Alfred Schmeller wrote the text. The original storyboard book with glued-in contact prints and instructions is also part of the holdings at OstLicht Collection.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Franz Hubmann, Pariser Parnass. Fotos zur französischen Kunstszene der fünfziger Jahre, Graz 1970; Hans Schaumberger (ed.), Franz Hubmann. Zeitgenossen, Zeitgenossen. Photographien 1950–1980, Vienna/Munich 1984, p. 110.

|

||

|

||

|

With his legendary »Pojechali!« (Here we go) the Russian Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space and people back on earth held their breath. The Russians had succeeded and, for the present, had won the technological race between East and West. Nevertheless, by 1969 it was an American, who set foot on the moon.

The photograph shows the young spaceman Gagarin during the process of getting dressed for his first flight into outer space. The photographer captured what was a rather intimate moment – the cosmonaut in a pensive attitude, not yet in his characteristic protective spacesuit. In the run-up to the greatest adventure a human had ever taken part in, Gagarin liked to show himself in public as intrepid and optimistic. Here he appeared to feel that he is unobserved which allows us to see the uncertainty of the impending journey written clearly all over his face.

Yuri Gagarin was born in Smolensk in 1934, and after being trained as a foundry technician, he underwent training as a pilot in the cadet training school of the Soviet air force in Orenburg until 1957. He was selected for the first Soviet team of cosmonauts and began training in March 1960. Because of his particular ability to withstand physical and mental stress, Gagarin was assigned to take part in the first manned spaceflight. On the 12th of April 1961 the 27 year-old Yuri Gagarin took off as the first human in space. He orbited the earth once on board the »Vostok 1«, taking 108 minutes. The elliptical flight path took him up to 237 kilometres away from the surface of the earth.

After his return he was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union and awarded the Order of Lenin. Thereafter Yuri Gagarin was a substitute pilot on the Soyuz 1 mission in April 1967 but he never returned to space. Yuri Gagarin died in an aeroplane crash on the 27th of March 1968 while undertaking a training flight with group captain Vladimir Seregin. Both men died in the crashed machine without having activated the ejection seat.

OstLicht Collection holds over 150 photographs of Yuri Gagarin. The group is part of the Space Collection consisting of more than 2,600 prints, covering NASA programs Gemini 3 to 12, missions Apollo 1 to 17, as well as other American and Russian space ventures.

Ulla Fischer-Westhauser, © OstLicht

|

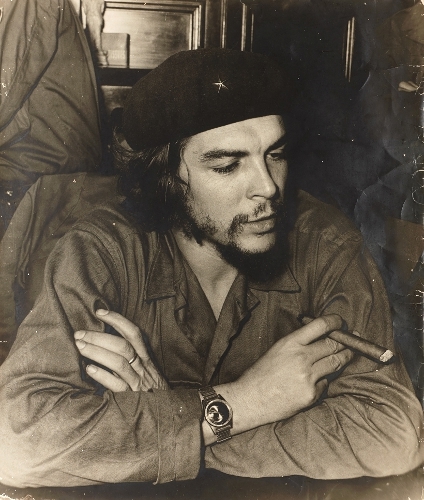

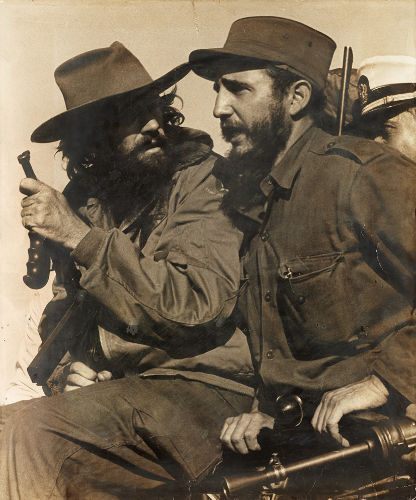

The main focus of OstLicht’s Cuban Collection is the Revolution: its origins in the 1940s and 50s, the Guerrilla warfare of the rebels and the »heroic« first years after Fidel Castro’s take-over of power. Portraits of protagonists, photo essays and press images, for instance in the Sierra Maestra or at the Bay of Pigs, as well as images of political rallies and acts of state, illustrate the moving history of the Revolution – but they also show the central role of photography in the shaping and distribution of its visual propaganda.

OstLicht holds more than 3,500 prints in its Cuban Collection. The different backgrounds and approaches of many photographers can be traced in large groups of monographic work. For instance, Alberto Korda is represented with over 300, Raúl Corrales with more than 130, and Osvaldo and Roberto Salas are represented with more than 200 prints. Other series in the collection by photographers of the next generation (e.g. Marucha, Mayito) stand for a new era of Cuban photojournalism.

|

||

|

After two years of guerrilla warfare the Cuban revolutionaries were almost in power. Ernesto Ché Guevara (1928–1968) and his troops achieved one of their biggest victories in 1958, the takeover of Santa Clara, where hundreds of soldiers of the Batista regime had been stationed. During the New Year celebrations, Batista fled the country and Fidel Castro ordered Guevara to move towards fort San Carlos de la Cabaña in Havana immediately, and to await him there. At the same time Fidel Castro started his famous march to lead his troops on from Santiago across the whole island. On the 8th of January, with the triumphant entrance of the rebels in Havana, all guerrilla leaders and soldiers reunited to celebrate victory in the midst of thousands of Cubans.

The picture shows Commandant Guevara sitting in his wood panelled office in the fort in Havana. After the celebrations of the following days, he will give orders for the executions of many Batista supporters from this office. Yet only after a few weeks, his asthma will force him to retire to a house at the beach. There he writes his book »La Guerra de Guerrillas«. While still in bed, he works on essential programs for the new government, like the expropriation of large-scale private estates, the agrarianreform, the foundation of a security service, as well as his first ideas for the »export« of the Revolution to other Latin Americas – a venture, which will eventually cost him his life.

Perfecto Romero was a 22-year-young when he joined the rebels in the Sierra del Escambray, and became the photographer of the troops of Ché Guevara and Camilo Cienfuegos. He took many extraordinary images, special because of their proximity to their subjects (and their motivations), amongst them many portraits of Camilo Cienfuegos. He is also well-known for his images of Ché from the final phase of the guerrilla fights, mostly showing the hero with a black arm sling after an injury in Santa Clara.

As many vintage prints as well as negatives of Romero were destroyed, his images still circulating are often grainy and blurry copies that were reproduced from his positives. This large format print in contrast is an image directly printed from the negative. The photograph is part of a well-known series, including a similar picture still decorating the place it was taken in, Ché’s office in the fort, which has been kept in its former state as a memorial to the Revolution.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Che-Earbook, Hamburg 2007, p. 71; Thomas Mießgang, Ché Guevara. Ich bin ein optimistischer Realist, Cologne 2007 (from the same series).

|

||

|

|

||

|

With the arrival of Fidel Castro and his troops in Havana on January 8, 1959, the victory of the Cuban Revolution was sealed. Effectively, all of the capital’s inhabitants were up and about to celebrate on the streets. Alberto Korda, who with his studio would become one of the most important photographers of the revolution – it is his image of Che Guevara that is counted as the most-reproduced photograph in the world –did not take any pictures that day, but watched the events from a balcony.

It was his studio partner Luis Antonio Peirce Byers, also known as Luis Korda or »Korda, the elder«, who mingled with the crowd – and actually got close to the open Jeep on which Fidel Castro and Camilo Cienfuegos entered the city. He took a picture in square medium format, which was later cut into portrait format by Alberto Korda (there exists a contact print showing his marks for the cropping).

The image is one of the icons of the history of the revolution and published widely. Particularly in Alberto Korda’s editing to portrait format it combines the two most important functions of photography in the Cuban Revolution: to report events (getting especially climactic during these days) and to provide powerful portraits of the revolution’s heroes. An early generation of photo-historical discussions on this period defined the term of the »epical phase«, in which photography supplies the pictures to tell a heroic tale.

Fidel Castro, who remained in power for decades and strongly determined the country’s fate, had a lot of time to refine the image cult of his own person (OstLicht Collection holds hundreds of photographs that impressively document that process). Camilo Cienfuegos was a young tailor joining the rebels in the Sierra Meastra and took on a major role in guerrilla warfare. Nine months after Korda studio’s picture, he died in a plane crash. Nevertheless, the cult of the charismatic man with the Stetson remains unbroken in Cuba, examplified on a public holiday with special rituals. His photographic portraits, often reproduced in postcard format similar to trading cards of stars are widely disseminated in Cuba.

Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Cristina Vives, Mark Sanders (ed.), Korda. A revolutionary lens, Göttingen 2008, p. 28, 40f.

|

||

|

||

|

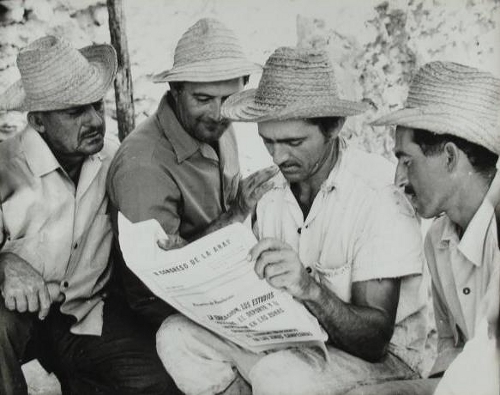

Alongside a reform of the social and healthcare-system, it was the revolutionary government’s major goal to improve access to education. In the times of Batista’s regime a fourth of the population was unable to read or write and the number of illiterates in rural areas was as high as 40%. Fidel Castro adopted ideas of the Cuban national poet José Martí when he defined the year 1961 as »Año de la Educación«, its core being the literacy campaign. This was made possible by the voluntary work of mostly urban adolescents and teachers, who as so-called »Brigadistas« taught the rural population within a year. By the end of 1961, the campaign was officially finished, having reduced the Cuban illiteracy rate to the lowest rate in Latin America.

Now capable of reading and writing, four men bend over a leaflet of the »Asociación Nacional de Agricultores Pequeños« (ANAP), an advocacy for Cuban agricultural workers which was also founded in 1961. Wearing the classic headgear for fieldworkers, the Sombreros, these men seem to make use of a break and catch up on political news. They form a contrast to pre-revolutionary documentarist farming scenes and genre photography, where the bitter poverty of the rural population clad in rags dominated. The scene, where the four men obviously follow a stage direction to mime interested readers, depicts Castro's policy different from iconic portraits of the revolution’s heroes.

Osvaldo Salas’ photo stories often intend to show the new, better Cuba. Raised in New York, where he was working for LIFE and other magazines as a photographer, Salas had made himself a name as a portraitist of Hollywood stars and artists, and by motifs from the world of boxing. In 1959 he returned to his homeland together with his 18-year old son Roberto. In the following years father and son became chroniclers of the Revolution and Osvaldo Salas became editor-in-chief at the photographic division of the party’s paper »Revolución«.

Isabella Riedel, © OstLicht Lit.: Con el espíritu de los Maestros Ambulantes. La Campana de la Alfabetizatión Cubana, 1961, Melbourne, New York, Havana: Ocean Press, 2001.

|

||

|

||

|

Unlike almost any other, Raúl Corrales was capable to visualise the requests, achievementsand the image of people shaped by the Revolution. A son of Spanish immigrants and sugar cane cutters, he worked as a shoeshine boy and a dishwasher before he was able to professionally turn to photography from the mid-1940s onwards. After the Revolution he became a member of the communist party and was active in the inner circle around Fidel Castro, alongside Alberto Korda and Osvaldo Salas. Corrales accompanied the »máximo líder« on a daily basis ever since his coming into power in January 1959. He is still regarded as one of the most important documentarists of the change of system and he has shaped the visual tradition of the Cuban Revolution decisively.

His photograph of a female revolutionary with an armlet draws references to several discourses approximately one decade after the takeover of power by Fidel Castro. The picture of an Afro-Cuban woman is not only a successful individual portrait, but also has symbolic relevance. Although unknown, she becomes a protagonist, a symbolisation of a new social order and the »face of the revolution«. Self-confident and thoughtful at the same time, the woman gazes beyond the margin of the picture. She is wearing a sleeveless blouse, an armlet, and has a cloth wrapped around her head. Her half-length figure contrasts with the dark background, in its upper left corner the letters of an illuminated advertisement can be seen.

Corrales’ visual concept supports the myth of the Revolution, including lasting achievements like female empowerment. Crucial for the process to gain gender equality in society was the work of the FMC (Federación de Mujeres Cubanas), a federation consisting of several women’s organisations under governmental control. In contrast to groups with specific interest like the FMC, there was no such organisation of the African minority after 1959. However, its legal parity with other ethnic groups was, as part of Cuba’s social change, still a decided aim of the philosophy of the Revolution.

Isabella Riedel, © OstLicht

|

Vienna Actionism emerged in post war Austria, a period dominated by restorationist sentiments and ostentatious Catholicism, when it was common sense to see Austria as a victim of National Socialism to repress the inglorious recent past. The avant-garde artists challenged the traditional notion of the artwork and the concept of representation, and pursued the utopia of changing society’s psychosocial structures through art. Their provoking performances (»actions«) broke taboos and tested limits.

The role of photography as the medium of recording was crucial, although the four protagonists of this movement used it in varying ways for their different approaches. OstLicht’s focus is mainly on the photo-actionist works by Rudolf Schwarzkogler (c. 440 prints), documentations of early actions by Hermann Nitsch (c. 340 prints), and on the Actionist period of Otto Muehl (c. 330 prints).

|

||

|

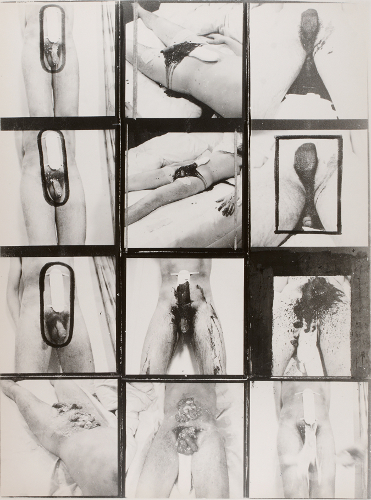

The dramaturgical meta-concept of Nitsch’s »Orgies-Mysteries-Theatre« (OMT) discerns his artistic approach from his colleague’s actionist work. His actions were (and still are) previously determined by minutely defined scores that direct the process of a ritual-like event –hence individual acts or whole actions can be repeated and newly combined. In contrast, Brus’s and Muehl’s actions areconceived as unique happenings. And Schwarzkogler’s actions, which are also precisely designed in advance, are staged for the camera, not as events for immediate reception or audience reaction.

In the early 1960s Nitsch formulated the dramaturgical elements of his OMT part by part. The central motives became already manifest in his earliest actions: the crucifixion (1st action in 1962), the tearing of the lamb (2nd action in 1963), or the Dionysian feast (»Festival of Psycho-Physical Naturalism« in 1963). In 1965 he added the new element of body collage, the »Penisbespülung« (the irrigation of the penis). During the procedure the penis of the protagonist is drenched in blood and eggs or covered in meat, intestines, and sanitary towels. In January of 1965 Nitsch drew up designs for the process that would be the first »Penisbespülung«, where all positions are minutely defined and described, including the exact angle the photograph should be taken from.

Since his 8th action, Nitsch elaborated the aesthetics and formal design of this motif, mostly without audience. Rudolf Schwarzkogler was his »Akteur« until the11th action. Photographer Siegfried Klein undertook the shootings and provided his contact sheets to Nitsch. For this image Nitsch accentuated 6x6 cm-contact prints with his felt pen markings and collaged twelve of them as a tableau. Later the collage was photographed and printed in an enlarged format.

Nitsch’s aesthetic preferences are clearly detectable here: instead of oblique perspectives, possibly evoking a dynamic image design or a shortening of the body’s representation, he prefers strictly rectangular compositions and camera angels from straight ahead or above. From the 11th action on, Nitsch had his penis-action's pictures taken by Franziska Cibulka, whose husband Heinz was to become Nitsch’s most important »Akteur« until 1975. She made more concessions to Nitsch’s expectations than Klein, who came to document many actions of Otto Muehl.

Michaela Seiser / Marie Röbl, © OstLicht Lit.: Viennese Actionism 1960–1971, Vol. 2, The Shattered Mirror, ed. by Hubert Klocker in cooperation with Graphische Sammlung Albertina Wien and Museum Ludwig Köln, Klagenfurt 1989, p. 275.

|

||

|

|

||

|

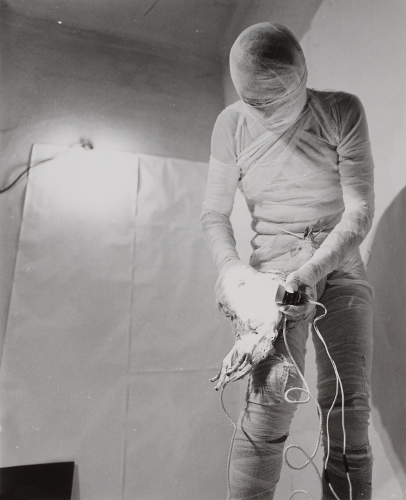

In the beginning of the 1960s Otto Muehl, a trained art educator and teacher of history and German language became a painter. Making the acquaintance of Günter Brus and Alfons Schilling, as well as their informal paintings in 1961, fundamentally influenced his work. Muehl’s paintings became abstract and focused on paint as material, in the sense of matter as the main creative material. He worked with his hands and feet, rolling over his canvases and ignoring all compositional doctrines. Eventually he started to rip the canvases and tied them up. His paintings became objects. He occasionally drenched his material montages, made from scrap iron and junk, in colour.

In autumn of 1963 Muehl executed his first action »Versumpfung einer Venus« (enmiring of a Venus) and extended his concept of material montage by human material. An important inspiration was Hermann Nitsch, who had already performed his first painting actions when Muehl met him. Muehl’s 3rd material action consisted of four parts: »Klarsichtpackung« (cling film wrapping), »Versumpfung in einer Truhe« (enmiring in a chest), »Panierung eines weiblichen Gesäßes« (breadcrumbing of a female bottom), and »Wälzen im Schlamm« (rolling in mud). This colour photograph shows a picture from the first part, where Muehl threw mud and paint onto the naked body of a woman, tied her up and then wrapped her in transparent film. Like most of his early actions, the performance ended with the dissolution and commingling of all materials, the so-called enmiring and what remained was brown pulp.

On the one hand, Muehl’s work was characterised by the uninhibited, intoxicating, creative act, where he was splashing dirt and paint over his pieces and included provocative sexual acts in his later period. On the other hand, he followed a painterly material aesthetics that he developed into still lives consisting of bodies and materials.

The photographic documents of the actions were part of the concept. Three photographers – Ludwig Hoffenreich, Siegfried Klein (Khasaq) and Alfred Haberler – as well as the cinematographer Peter Jurkowitsch participated in documenting the third material action. For his most sumptuous portfolio edition Muehl chose only pictures taken by Hoffenreich, as they were closest to his intention of presenting an intermingling and unification of all materials, where the human body appears as an object amongst many.

Michaela Seiser, © OstLicht Lit.: Viennese Actionism 1960–1971, vol. 2, The Shattered Mirror, ed. by Hubert Klocker in cooperation with Graphische Sammlung Albertina Wien and Museum Ludwig Köln, Klagenfurt 1989, p. 185–190; Eva Badura-Triska, Hubert Klocker (ed.), Vienna Actionism. Art and Upheaval in 1960s’ Vienna, cat. mumok Vienna, Cologne 2012, p. 82.

|

||

|

||

|